When I was growing up in Apartheid South Africa, the loss of a Black life was not something that necessarily translated to prosecution or justice for the victims. This was in the 80s. It is outrageous to know that this is still true for Black people in 2020.

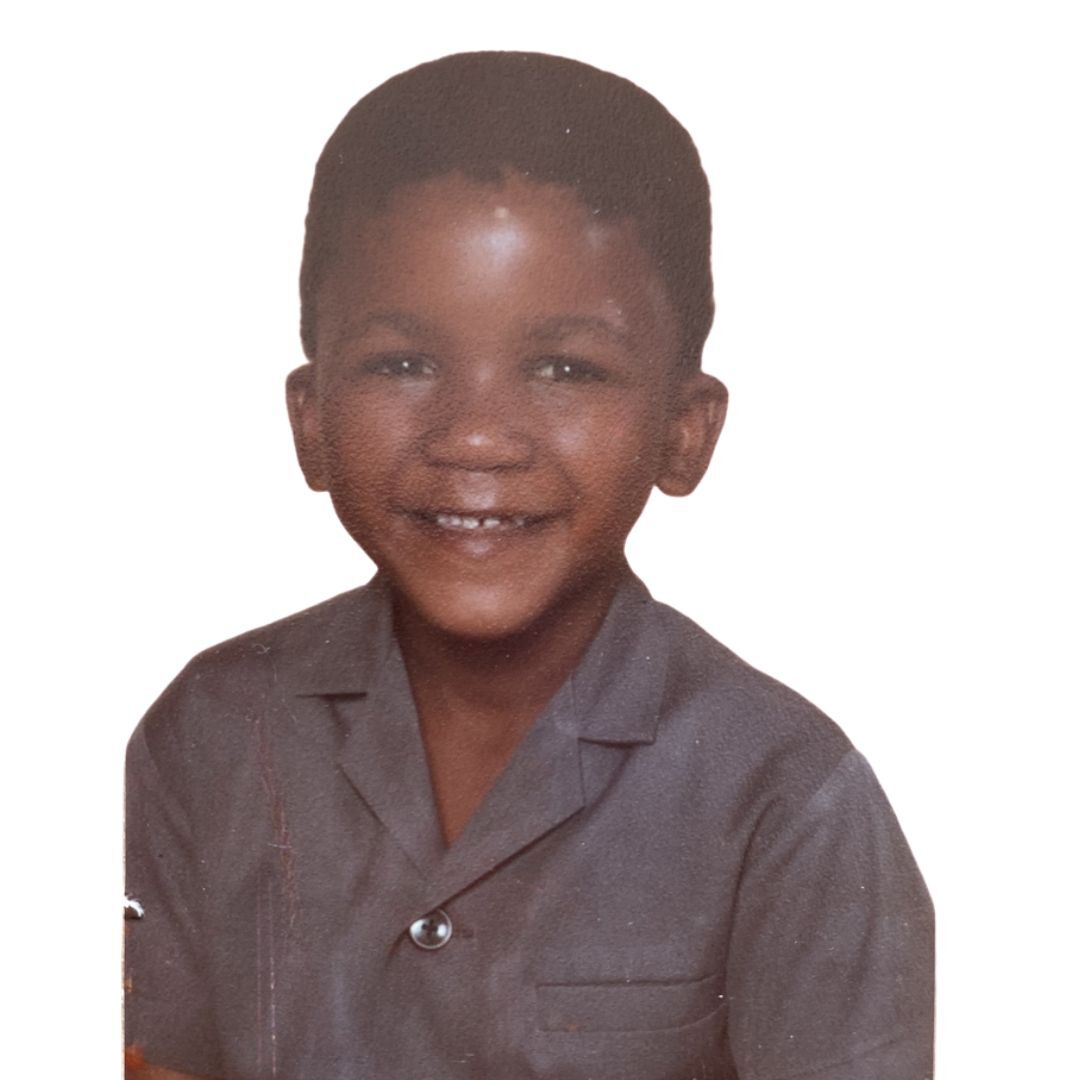

I was born in South Africa during Apartheid. Apartheid South Africa was all about racial labels. The broad category my family fell into was called non-White which covered 90 % of the population. The specific category we fell into was called Coloured – a classification for all people of mixed origins.

In the race hierarchy, Coloured people were not as acceptable as White people, but were definitely more acceptable than Black people. Black people were treated as inferior and regarded as sub-human in South Africa.

Segregation in South Africa determined where you could live, what jobs you could get, your healthcare, and the infrastructure and resources you had access to. Signs with the words “WHITES ONLY” were commonplace, making it really clear where you were welcome (or unwelcome) according to the colour of your skin.

State schools were segregated by race and non-white pupils received inferior education by law. But my parents chose to send my sisters and I to a private school where students of all races were welcome if their families could afford the school fees. I was somewhat sheltered from the harsh realities of segregation and I couldn’t imagine a school without children of all races.

As a child, I would sit in my classroom alongside children of all races – Black, White, Coloured and Indian (official South African classifications). As an adult, I realised that I had no idea what life was like for the Black kids in the same room as me.

About a year ago I asked a Black friend, who I went to secondary school with, about his experience during that time and this is what he shared:

From the superficial yet symbolic relative treatment of the family pet versus the gardener: (Dog sits in the warm passenger seat while gardener sits in the back of the van in the Winter wind) to the ultimate examples that informed the exile movement of the time.

People weren’t going into exile because they feared jail… they moved into exile because they feared death.

The death of a black person at the hands of the state was an act almost guaranteed to have no consequences for those who carried it out – and we all knew it.

My Dad was a journalist in the ’80s and was summoned to appear in court because he had been in the presence of, and written about some freedom fighters, who were on trial. When he travelled to the Transvaal from the Free State, the police raided the house back home where my mother was… no warrant, no warning. They turned the house upside down looking for any piece of evidence that could tie him to the accused on a personal level and expose him as being a conspirator.

I remember as recently as my primary school years … I was home from school, late afternoon/early evening. Suddenly the entire township was stirring with activity – cops were chasing kids (literal school kids) and beating them with batons, some were being trampled in the melee, others were bleeding from their wounds, kids were running into our house asking for shelter… all because they had participated in some protest action the week before. I was always struck by how the police were hunting down kids with no fear of opposition in the flimsy excuse we had for a sanctuary: our very homesteads.”

– Lebo Mochudi

The reality of people who are different from us needs to be heard and acknowledged. And how people experience their reality needs to be respected.

No person deserves to live in fear for their lives. No person deserves to be treated as less than human because of the colour of their skin.

As a psychotherapist, I am invited to hear and hold people’s most vulnerable experiences. I am invited to sit alongside them as they dare to explore their most painful feelings. As a person of colour from South Africa, I have my own pain to deal with. I fully absorbed the belief that I don’t deserve to be valued or respected. And I know that, for Black people, this is much worse.

Yes, there’s hope, there’s positive outlook, there’s moving forwards, there’s focussing on, growth and healing, etc. And at the same time, we have an opportunity now to make space for Black voices to be heard. Hearing people’s pain does not mean that we have to stay stuck there. There is a way of shifting out of the pain. But before change can happen, there must be understanding.

The most important thing I’ve learnt is to find compassion for myself first and to then find empathy and compassion for others. Without judgement. And without defensiveness.

Let’s first seek to understand, with deep compassion for others, and then use our rage and grief to create an impact where it matters most.

Black Lives Matter.

If you have a story to share with us here at NISAD, please let us know.

Janine Miller

Clinical Director at NISAD Lund, Sweden

MSc Psychotherapy, Certified Transactional Analyst (CTA)

NISAD in solidarity with protests against racial injustice

In light of recent events in the United States and the much-needed attention given to systemic and institutionalised racism worldwide, NISAD would like to emphasise that we refuse to accept discrimination and prejudice based on skin colour.

We acknowledge the pain of Black people now and in the past. Racism erodes the fabric of society and the psychological impact of this inter-generational trauma continues to cause harm and suffering for many.

This is a global problem; this is a local problem. Wherever we are, this needs our continued attention. We embrace the challenge to demand greater accountability from ourselves, from the authorities, from lawmakers, from communities and from individuals. The continued treatment of Black people as inferior or sub-human must be addressed. This is a message the world needs to hear over and over again until there is equality, fairness and justice.

Experiencing racism has a detrimental effect on both mental health and overall health.

Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups are identified as being of high risk of mental health problems due to discrimination and socio-economic inequalities.

At NISAD, we believe that everyone has the right to access emotional support, and that that this emotional support is either free or affordable and available quickly. In creating our programmes of support, we commit to being deeply mindful of difference and diversity as we work to support emotional and mental distress. In conducting our research, we commit to addressing the issue of under-representation of people from a BAME background.

Let’s all commit to joining the collective dialogue, to using our voices to spread compassion and understanding, and help end racial injustice for all BAME communities.

#BlackLivesMatter